HISTORICAL SCHOLARS

across the planet- anthropologists, conservationists, and humanitarians have shaped our understanding of what it is to be human. have a look at just a few legendary scholars WHO HAVE provided groundbreaking discoveries.

MARGARET MEAD | ANTHROPOLOGIST

Margaret Mead was an American anthropologist best known for her studies of the peoples of Oceania. She also commented on a wide array of societal issues, such as women's rights, nuclear proliferation, race relations, environmental pollution, and world hunger.

JANE GOODALL | CONSERVATIONIST

Ethologist and conservationist Jane Goodall redefined what it means to be human and set the standard for how behavioral studies are conducted through her work with wild chimpanzees in Gombe Stream National Park, Tanzania.

TOBIAS SCHNEEBAUM | ANTHROPOLOGIST

Tobias Schneebaum was an American artist, anthropologist, and AIDS activist. He is recognized for his experiences living and traveling among the Harakmbut people of Peru, and the Asmat people of Papua, Western New Guinea, Indonesia, then known as Irian Jaya.

ZAHI HAWASS | EGYPTOLOGIST

Zahi Hawass (born May 28, 1947, Al-ʿUbaydiyyah, Egypt) is an Egyptian archaeologist and public official, whose magnetic personality and forceful advocacy helped raise awareness of the excavation and preservation efforts he oversaw as head of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA).

the future in preservation

explore ancient artifacts with your fingertips from every angle in life-size scale

The National Gallery of Australia (NGA) to create a new way for visitors to interact with the artefacts in the Myth + Magic: Art of the Sepik River, Papua New Guinea exhibition. By developing a new 3D content platform that uses open web standards, the physical exhibits have been transformed into fully interactive digital sculptures.

This exhibition showcases the unique cultures of the Sepik River region of Papua New Guinea, a country that has been part of Australia's history and will very much be part of its future. Myth and magic opens as Papua New Guinea celebrates its 40th anniversary of independence. Go on, explore.

BIOGRAPHIES IN BONE

Skulls, skeletons, death masks, mummies, bones from a 19th-century plague pit and an axe-cleaved Iron Age skull. Some of the items in the University of Cambridge's Duckworth Laboratory -- one of the world's largest repositories of human remains. Hear about some of the stories -- the biographies in bone -- that are unfolding through research on this fascinating collection, including the analysis of the diet and journeys taken by pre-Dynastic Egyptians who lived in the Sahara Desert thousands of years ago.

The Duckworth Laboratory at the Leverhulme Centre for Human Evolutionary Studies is dedicated to the study of human and primate anatomy and anthropology

Cite: Leverhulme Centre

RAMBARAMPS | Ancestral Effigy

It is considered the most powerful part of the body and is often preserved as a relic after death. Among Solomon Islanders, for instance, fish-shaped reliquaries are created to house the skulls of important male ancestors. In Vanuatu, an archipelago near New Guinea, the skulls of the dead become the central component of life-size effigies called rambaramp.

Rambaramp were created only for men and only for those of the highest rank, usually chiefs or warriors.After death, the skull was removed, modeled over with clay, and attached to a surrogate body created out of bamboo, clay, and plant fibers. Once completed, the rambaramp would be set up in the men’s house, offering a place for the spirit to reside, continuing the presence of the ancestor, who would, in turn, ensure the well-being of the community. Because they were made largely of vegetal materials, the bodies of therambaramp would eventually decay. However, the skull—the most vital part of the figure—would continue to serve as a representative of the ancestor long after the body was gone.

Cite: www.learner.org/Cite: www.learner.org/

A Moai Kavakava Ancestor Figure from Easter Island

Oceanic art specialist Bruno Claessens explains how this wooden figure — brought to Europe in 1868 from the most isolated island in the world — has had an impact on art history that resonates far beyond its mysterious origins. For centuries, explorers and archaeologists have speculated about the enigmatic giant stone statues on Easter Island. Explanations for their existence have ranged from the idea that they were offerings to the gods to the theory that they marked freshwater sources.

The Hooper moai kavakava figure, Rapa Nui, Polynesia. Height: 44 cm (17⅜ in). Sold for €850,000 on 10 April 2019 at Christie’s in Paris

Cite: Christies.com

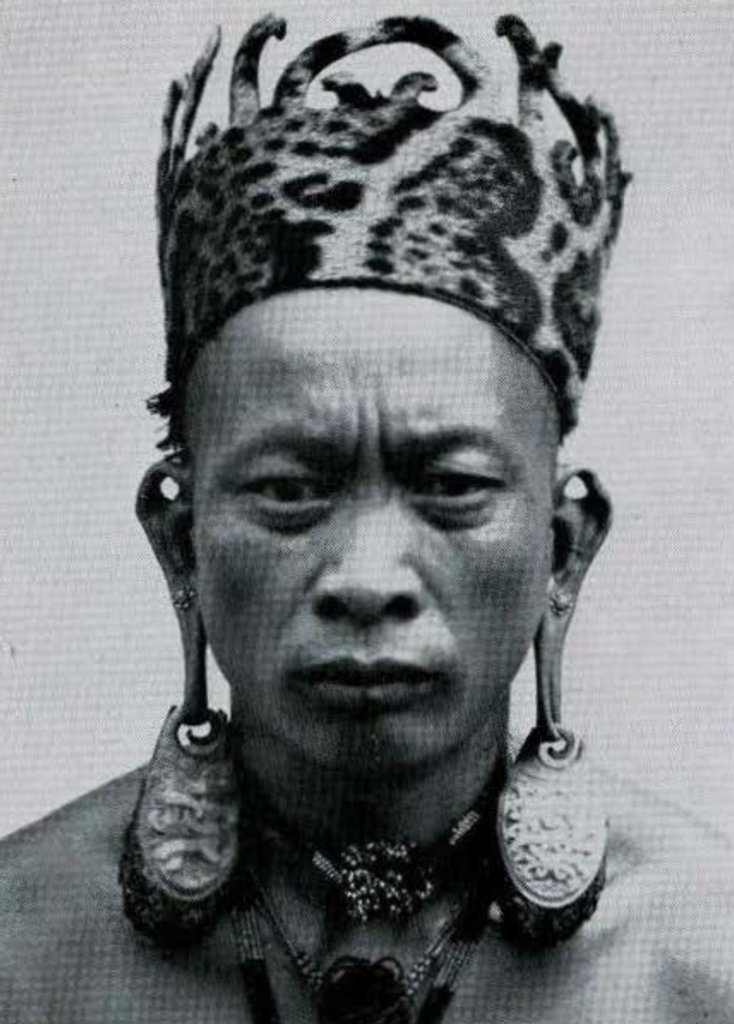

The Story of Hornbill Ivory

The strange substance called “hornbill ivory” was formerly an important commodity in Asiatic trade, and it was extensively carved, especially in China and the East Indies. Carvings in it were always highly valued and they have now become exceedingly rare. Thus we are very fortunate in having a fine example in the several museums such as the Penn University Museum.

There are at least sixty varieties of Hornbill birds in the Eastern Hemisphere, but only one of these bears the “ivory,” a hard, carvable substance which is almost as dense as elephant ivory. This is contained in a solid casque or epithema at the front of the head above the beak. (The casques of several other species of Hornbill are far more imposing, but they are hollow or filled with spongy tissue.) The single exception is the Helmeted Hornbill, Rhinoplax vigil.

The Helmeted Hornbill is without doubt the most extraordinary member of a remarkable family. It is not only one of the largest birds in the jungles of Southeast Asia, measuring nearly five feet from the end of its beak to the tip of its tail, it has coarse plumage, primarily of a dirty reddish black, except tor a white stomach and white bands on its tail. It has no feathers at all on most of its neck and back.

Read More: https://www.penn.museum/sites/bulletin/3367/